Music by Elton John; Book and lyrics by Lee Hall. Sydney Lyric Theatre, The Star. 18 Oct 2019 to 15 Dec 2019

Reviewed : 18 October 2019

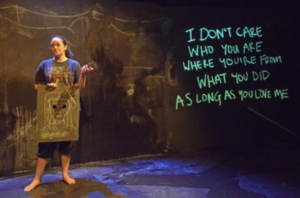

Billy Elliot The Musical returns to Sydney in a creatively designed production that captures the hope and ambition of a twelve-year old boy caught up in a political situation that almost brought Britain to civil war.

When Margaret Thatcher won power in 1983, she was determined to privatise the coal mining industry and bring down the powerful National Union of Mine Workers. The result of her policies led to a year-long strike and horrific clashes between miners and police – and a despair that spread across the nation.

Screen writer Lee Hall experienced that despair and encapsulated it in the movie Billy Elliot. When it premiered in Cannes in 2000, Elton John was in the audience and was so moved that he approached Stephen Daldry about the idea of a musical. Daldry took the idea to Hall who thought the idea was “rubbish”. But the suggestion came from Elton John! And “there was a tradition of musical theatre that embraced all the things that Billy Elliot was about. They made a pact to do the musical “so long as we would not short-change the material emotionally or physically”.

Unlike many musicals, the dialogue drives the action, giving greater dimension to the characters and sustaining the sense of reality and the emotional core that Hall worried might be lost. John’s music picks up the rhythm of protest, and choreographer Peter Darling uses it to create a “celebration” of all kinds of dance, especially tap, which infuses the show with an element of immediacy and anger. Nowhere is this more evident than in “The Angry Dance”, when Billy responds to his father’s order to give up dancing.

Darling’s choreography is creative and emphasises the emotionally charged motifs in the music. For example, the slick, repeated gestures of the stiff, regimented “Bobbies” as they stand at attention; the horror of police shields advancing on the miners; the poignant use of empty space between Billy and a vision of his dead mother in “The Letter”; and the sheer joy of movement in “Born to Boogie”.

Darling breaks with tradition in his ballet choreography, infusing it with hip hop movements, acrobatics and discordant angles, especially when Billy dances to “Electricity” in his Royal Ballet audition.

All of this must be exhilarating for the cast. There is a sense of urgency in their performances, enhanced by the realness of their characters and the story. Even the ballet school is an integral part of the story, the young dancers required to be “real” students.

Billy, as the central character, must be actor, dancer and singer. Jamie Rogers got the chance to show his talent in all three areas on Opening Night, but Omar Abiad, River Mardesic and Wade Neilsen will charm audiences just as thrillingly in future performances. It was good to see all four boys take a bow together in the Opening Night finale.

Justin Smith finds emotional turmoil in the role of Billy’s dad, single father, striking miner, battling provider, torn by traditional values and his realisation that his son might have a different future.

Kelley Abbey shines as the encouraging but flinty Mrs Wilkinson. Vivien Davies uses comedic timing to create a knowing Grandma. Drew Livingston, as Tony, symbolises the righteous indignation and anger of the striking miners, and Robert Grubb brings humour to the role of boxing instructor George.

The company works as a united ensemble, raising the tension in song and movement as the action accelerates and tempers rise. There are some beautifully executed scenes, where police and miners act and interact in carefully fused choreography. Especially moving are the miners retreating to the pit, their backs to the audience, their despair in defeat such a contrast to their solidarity in protest.

The orchestra, led by Michael Azzopardi, finds both the rage and rebellion Elton John has infused into the score – and the naivety and hope of Billy and those who believe in him.

The political situation that Billy Elliot revisits is one that could well happen again. Billy’s dilemma is one that is still faced by many young male dancers. Every reprise of both stories may help change the world.

Also published in Stage Whispers magazine