By George Frideric Handel. Words John Milton and Newburgh Hamilton. Sydney Philharmonia Choirs. Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House. Saturday 8 April, 2023

Reviewed : April 8, 2023

Handel’s Samson! In the Concert Hall of the Opera House! On Easter Saturday! Wow!

It’s aways a thrill to see and hear the Sydney Philharmonia Choirs – as anyone of the audience of the 1250 ardent Philharmonia followers will testify. But this one was special, and it’s hard to find the appropriate adjectives! Stunning? Magnificent? Superb? Dramatic? All of those and more. And yet the music was written by Handel in 1741 to words written by the poet John Milton from 1671 – and they were based on words from the book of Judges in the Old Testament of the Bible written between 1200-165 BCE! That’s remarkable! As was yesterday’s performance.

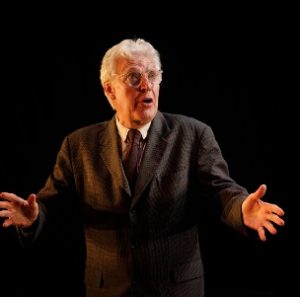

In his 20th year as Artistic and Music Director of the Sydney Philharmonia Choirs, Brett Weymark led his choir, the orchestra and seven very talented soloists in Handel’s musical re-telling of Samson’s final days … and his last triumphant act of strength.

Who was Samson? Samson was the last judge named in the Book of Judges. He died in 1051 BCE when David was the king of the Israelites. He was celebrated for his feats of strength but ended up blind and in chains, betrayed by his wife Dalila to whom he disclosed the secret that his strength lay in his long hair. One night, as he slept, Dalia cut off his hair and betrayed him to her Philistine compatriots, who captured Samson, put out his eyes, and imprisoned him.

Handel’s oratorio tells of Samson’s regret at falling for Dalila’s wiles, giving away his secret and letting down the Israelites. It tells of his rejection of Dalila’s apology, of his reckless challenge to fight the giant Philistine soldier, Harapha, and concludes with Samson regaining his strength enough to destroy the Philistine temple – and, alas, himself.

Unwounded of his enemies he fell,

At once he did destroy and was destroy’d;

The edifice where all were met to see,

Upon their heads, and on his own he pull’d!

It’s a story characterised by betrayal, loss of self-esteem, despair, and death … but eventual triumph. Milton portrayed that in words, Handel transformed them into music that took them to more complex dimensions – all of which resounded superbly in the Concert Hall yesterday.

Particularly superb was the performance of Alexander Lewis as Samson. Lewis sang heart-wrenchingly of the despair of the man, bereft of his power and his sight, languishing in prison – but he also became the man and his anguish when he was not singing. His eyes stared into a lonely space; his body seemed to carry the weight of suffering. It was a memorable performance that was deeply moving. (He will sing with the Philharmonia in the Concert Hall again in The Golden Age of Broadway on Saturday 6th May at 7pm).

Samson’s friend Micah was invented by librettist Newburgh Hamilton to narrate the story as a sort of Greek Chorus, and countertenor Russell Harcourt performed this long and exacting role with aplomb, finding Handel’s musical perception of the poet’s words in lines such as …

Ye sons of Israel now lament …

Your glory’s fled

Amongst the dead

Great Samson lies

For ever, ever, clos’d his eyes!

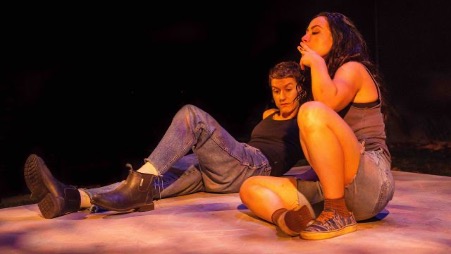

Soprano Celeste Lazarenko, as Dalila, charmed the audience as she sang (and played) the shamed, apologetic wife, rather than the “hyena” Samson described whose “charms to ruin led the way”.

Manoa, Samson’s proud but devasted father, was performed by bass-baritone Christopher Richardson, who found a father’s anguish in his carefully modulated notes.

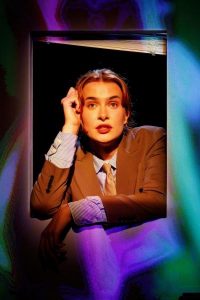

Perth-born Andrew O’Connor made his debut at the Sydney Opera House singing the boasting Philistine “giant” Harapha. O’Connor’s powerful bass voice taunted Samson in his “chains” but met his own fate at Samson’s hands when Samson felled the Philistine temple.

T

enor Matthew Flood was the messenger describing Samson’s death – and introducing the beautifully sombre dirge with which Handel heralded Samson’s hearse. Here, Lazarenko returned to the stage as an Israelite woman, calling the Virgin Choristers – and Irish-Australian soprano Stephanie Mooney – as they brought the “laurels” to strew on the hearse.

Behind the soloists, supporting them constantly, was Weymark, the orchestra and the watchful, wonderful one hundred and five singers of the Philharmonia Chorus. Together their voices rang out in praise at times, in sadness at others – and joyfully as they “let their celestial concerts all unite” in the final moments of the oratorio.

It’s always special to watch Brett Weymark at work. His love of the music is evident in vibrant enthusiasm and his extraordinary relationship with each part of orchestra and every member of the choir. This performance was no exception. Together with the soloists, they made this interpretation of Handel’s musical characterisation of the bible story much more than a ‘performance’.

Also published in Stage Whispers magazine.