By Stephen Sewell. White Box Theatre in association with bAKEHOUSE Theatre. KXT on Broadway. Oct 27 – Nov 11, 2023.

Reviewed : 5 November, 2023

The text in this latest work by Stephen Sewell is almost as dense as the lengthy treatise on the work of psychiatrist Jacques Lacan that is made available to audience members should they have the time or inclination to read it. After seeing the play, I decided to take that time in order to see if the information therein might change my ‘gut reaction’ to the production. It explained in some detail Lacan’s complicated theories about the development of ‘self’ – aptly described by some as “novel’, ‘complex’, ‘obscure’ and ‘enigmatic’ – and his methods of psychoanalysis, which shed light on some of the ‘clinical’ staging and blocking used by director Kim Hardwick.

However (and I know it is grammatically incorrect to begin a sentence thus) it would have been better had I used the reading time to write from the ‘gut’ because, though I now see how many of Lacan’s theories and practices have influenced Sewell’s writing, I still can’t see the need for the concentrated and intensely convoluted dialogue. All the ‘theories’ were there in the characters, their frailties, and their fraught relationships, but they were made heavy by trying to make them exemplify too many of Lacan’s “diagnostic categories”.

Don’t get me wrong, the cast handled that dialogue superbly and the tension they developed under Hardwick’s direction was tight and oppressive – almost as oppressive as the heavy red Persian rugs that enveloped the set. The overall mood of the production was one of despair, though lightness came in some humorous exchanges and the appearance of a ghost.

“Distance” was a feature of the production – distance between patient and practitioner, distance between husband and wife, distance between mother and daughter. Hardwick stretched the small transverse stage at KXT to make that distance taut and wired with tensions that kept the characters edgily wary of each other.

Helen O’Connor as Eve, the Lacanian psychoanalyst, carries much of the dramatic burden of that tension – in her consulting room and at home. O’Connor holds herself tightly throughout the long first act but becomes increasingly strained in both her seeming lack of empathy with her client, Sylvia, and her husband. She shows this in her stance, the way she holds her head, her fixed, guarded eyes. With Sylvia she sits out of direct sight and listens rather than asking questions – as Lacanian practice suggests – but her reactions to Sylvia’s words seem personal rather than clinical and detached. The reason is obvious later in scenes with her husband, Paul.

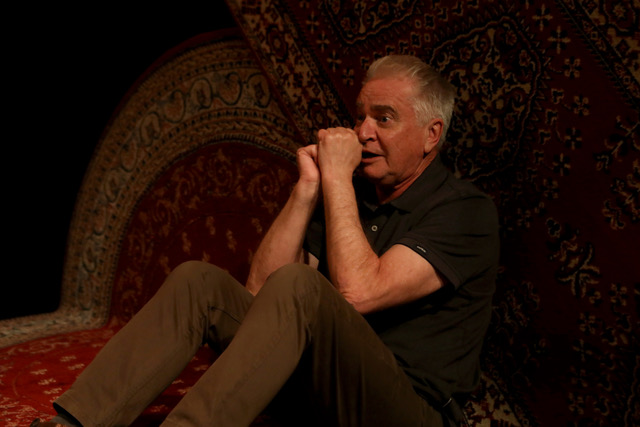

Paul, played by Noel Hodda, is gentle, forbearing but beleaguered by Eve’s lack of warmth and the distance she keeps between them. It is a difficult role and one Hodda plays well, continually reaching across the distances and taking Eve’s rebuffs with gentle understanding that hides growing hurt and dismay.

Louisa Panucci plays Sylvia. Confused, but erudite, she wants answers, but knows that Eve, as a Lacanian, listens rather than asks questions. And Sylvia is happy to talk … about her sex life, her friends, her relationships … but really she wants Eve to explain rather than let her find out for herself. Panucci finds all the frustration that Sylvia feels, her developing irritation, her continuing disappointment, her growing anger with Eve. It is a difficult role, filled with emotional ups and downs that Panucci handles skilfully.

Annie Byron plays Madeline, the ghost of Eve’s mother, a quiet, gentle ghost that is Eve’s own ‘Lacanian analyst’, who listens, sometimes quizzically but always sympathetically. The appearance of Madeline in the second act breaks the oppression engendered in the long hard scenes in Act 1, and Byron, drifting into the darkened set, drink in hand, brings a muted ‘mauve-ness’ that lightens the tension and shows another image of Eve. There is humour in the comfort of their ‘conversation’ and the succour Eve seems to gain from it.

The gentleness of that scene fades quickly as further confrontations between Paul and Eve – and Sylvia and Eve – lead to revelations that are unexpected … and though contrived, give some theatrical denouement to the production.

This play is about women and their feeling, frustrations and follies – but they are drawn out too analytically, too bleakly.