Book, Music, Lyrics Richard O’Brien. Rocky Horror Company. Director Christopher Luscombe. Theatre Royal, Sydney. Opening Night: April 3, 2024

Reviewed : 3 April, 2024*

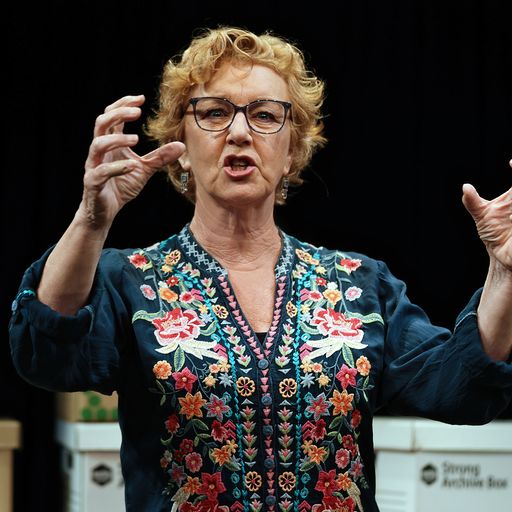

Richard O’Brien calls his creation “a celebration of wonderful rainbow joy and toe-tapping happiness” – but he knows it’s really much more than that. It’s brazen and boisterous; cheeky and colourful; loud and lively! And though I was probably one of the oldest people in the audience at last night’s opening performance, I was just as hyped as any of the other excited Sydney siders who packed the Theatre Royal to celebrate fifty years of The Rocky Horror Show.

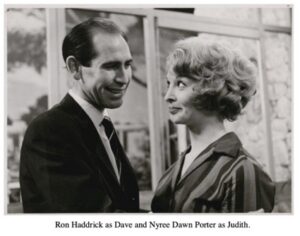

Since it opened in a little 63-seater theatre upstairs in the Royal Court in London in 1973 it’s been wowing audiences around the world. And it has s special place in Australian theatre history. It was Australia’s ‘showman’ Jim Sharman who directed Richard O’Brien himself as Riff Raff in the original London production; Sharman who directed it for Harry M. Miller a year later in Australia; and Sharman who encouraged Australia’s original Frank N Further Reg Livermore to be, in Reg’s words, “the fearless embodiment of all that is unspeakable”.

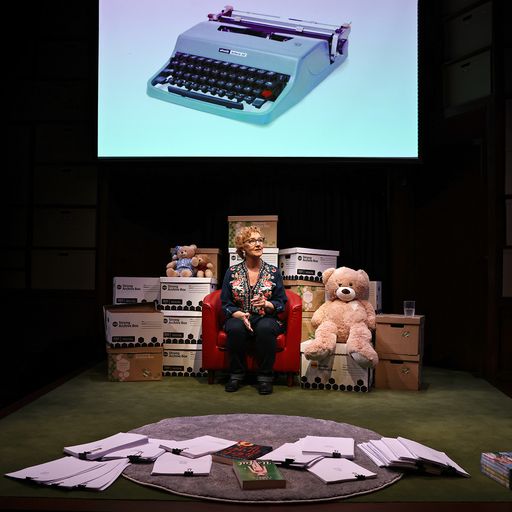

Jason Donovan does Livermore’s “fearless” Frank proud in this glittering production that sparkles with all the pizzazz of 21st century technology, creativity … and inclusivity. Because it is superstar tennis Paralympian Dylan Alcott OA who plays the Narrator, spinning his wheelchair on a different stage and, in his usual, confident style, returning the serves of hecklers with crisp, cross-court cuts.

From high above the stage, almost hidden behind the backdrop of a giant strip of celluloid film paying tribute to the B-grade Science Fiction “late night, double feature, picture shows” on which the musical is based, the musicians strike up and the Usherette – Voice finalist Stellar Perry – appears, and with her tray of ice creams to open this anniversary production.

Nick Richards returns to Sydney to light the show with multiple contemporary effects. Gareth Owens matches them with exotic wrap around sound, and Sue Blane adds more spangles, sequins, feathers and weird wigs to her original designs, to make them even more daringly bold and suggestive.

Wearing them is a cast that appears just as lively and excited as the audience that awaits them. Blake Bowden replaces his Opera Australia Phantom mask with black-framed spectacles to become a very bewildered 1970s Brad, and Deidre Khoo is, as she proclaims in her bio notes, a “loud and proud Asian Janet”. Both find the naïve simplicity of their characters with some nice ‘engagement’ harmonies and excellent comedic timing, especially as they enter the laboratory of Dr Frank N Furter and his strange staff.

Henry Rollo sidles and simpers as Riff Raff, his lithe suppleness emulating the wraithlike spookiness with which O’Brien himself imbued the character. His Phantoms – Josh Gates, Hollie James, Nicolas Van Litsenborgh and Erica Wild – slither and snake as his dark minions, always in perfect time and voice. Stellar Perry returns as his sister, the alluring Transylvanian temptress Magenta, and Darcey Eagle is a feisty and spirited Columbia who follows her transvestite hero with lusty vocals and driving energy, especially as she joins Riff Raff, Magenta and the Phantoms for the much-awaited “Time Warp”. Nathan M. Wright’s fast, contemporary choreography delights the audience, especially in the reprise at the end of the show where the Narrator adds a surprise!

Ellis Dolan rocks in the role of Eddie – yet plays things much more sombrely when he returns to the stage as a slightly ‘restrained’ Dr Scott.

Who have I missed? Oops! The mad transvestite scientist Frank N Furter himself … and his ‘perfect’ invention Rocky.

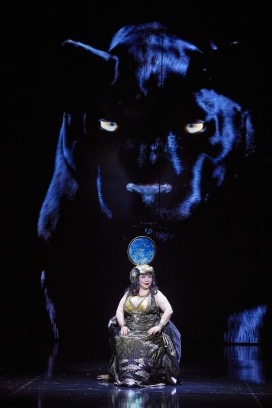

Jason Donovan is a dynamic, decadent Frank who owns the stage from the moment he strides in and throws off his black coat to reveal the corset, fishnets and pearls that are Frank’s ‘livery’! Strutting in high heels, he menaces the audience, never missing the opportunity to wriggle his eyebrows, flick his tongue or lustily lick his lips. Donovan brings a wealth of theatrical experience to the Rocky Horror stage. As well as playing Frank for the twenty-fifth anniversary production, he has sung for a monarch, and played characters as diverse as an Egyptian pharaoh and a drag queen. This performance shows he has lost none of the energy or charisma with which he has captured audiences here and overseas.

And Rocky, the mad medical transvestite’s “favourite obsession”? That’s Daniel Erbacher! He emerges from the circle of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man in sculpturesque splendour, complete with glittering gold bikini briefs and boots. Fresh-faced and wide-eyed, he poses innocently – well almost! – setting Janet’s heart fluttering and Brad’s fists clenching. Erbacher does a fine job with this role, making Rocky gloriously guileless and just a little god-like!

This “golden” anniversary of the Rocky Horror Show is a celebration of how a crazy idea based on some third-rate movies has become a musical theatre ‘icon’ that can be ‘dressed up’ in all the glitter and glam of modern theatrics, but never loses its original wicked artless appeal.

Long may it keep making us take the “jumps to the left” that make the sassiness of Rocky Horror so time-warpingly popular!

First published in Stage Whispers magazine

*Opening night