By Kirsty Marillier. Director: Zindzi Okenyo. National Theatre of Parramatta. Riverside Theatre Parramatta. 30 March – 2 April, 2022.

Reviewed : 30 March, 2022 (Opening Night)

Kirsty Marillier is a new, young writer who has honed her style carefully. “It’s not often you come across a new writer that already possesses such a unique and well-formed writing style,” writes director Zindzi Okenyo.

In Orange Thrower Marillier has crafted a play that speaks buoyantly about diversity, difference, assimilation, the yearning for acceptance and the exhilarating power of determination. It is acutely honest, wittily satirical, and delightfully funny. Her writing is succinct. She draws her characters deftly. They are cleverly authentic – in the way they relate, the words they speak, and the way they speak them. Okenyo and her cast make them live in a production that is bright, fast-paced and expressive.

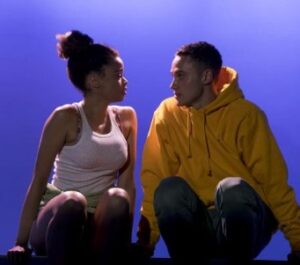

Marillier has set Orange Thrower in a fictional suburb in Perth called … Paradise. The play centres around Zadie, a young, coloured South African girl, her sister Vimsy and Leroy, Zadie’s boyfriend. Zadie is acutely aware of fitting in to the neighbourhood – and not doing anything to attract the attention of their disapproving neighbours, Sharon and Paul. When their cousin Stekkie appears mysteriously from Johannesburg, life becomes a bit more complicated – and noisier.

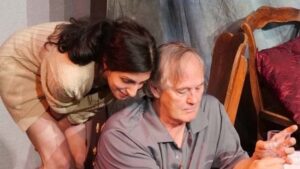

Zadie carries a lot on her young shoulders. As a nurse, she works hard, long shifts. As a sister, she is caring and concerned, and feels the reputation of her family resting heavily on her young shoulders. Gabriela Van Wyk incorporates all of this in a performance that is engaging and believable. She sustains an energy that defines the resilience and inner strength of the character she plays. The Zadie she creates is youthfully bright but sensibly mature, carrying her multiple responsibilities with an enthusiasm and positivity that is buoyed by innate optimism – and the affection and constancy of Leroy, played by Callan Colley.

Colley is breath of fresh air! He is an astute performer who finds every delightful quirk that Marillier has written into this role. His Leroy is proudly, boyishly masculine yet beguilingly insecure – and so anxious to please that he opens himself up to all sorts of misfortune. Colley uses the stage confidently and, as Leroy, establishes relationships that are believable and touching.

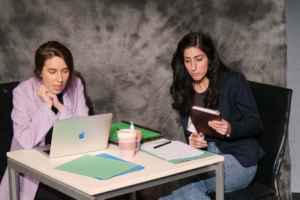

Mariama Whitton springs exuberantly into the role of Vimsy. Just out of school and working part time, Vimsy is itching for fun, and Whitton makes her a bit cheeky and defiant, energetic, game for anything, anxious to feel accepted. So, when Stekkie appears out of the blue – a ‘grown up’ who is brazen and sassy – Vimsy is ready to follow her lead.

Okenyo directs herself in the role of Stekkie. “I have never had such a visceral response to a character,” she says. “Living inside Stekkie’s brain was wild … I felt frightened and yet somehow without fear”. Rightly so, because Stekkie is volatile, spectral – an unpredictable Puckish character who switches mood erratically. Okenyo finds all of this, dancing crazily one moment, searching introspectively the next … like “a child with no place to fit”.

Marillier sprinkles her insights into “womanness, blackness, colouredness, otherness and youngness” and in-betweenness with clever humour – and cunning satire.

The neighbours – Sharon, and, briefly, her husband Paul – are played by Colley and Okenyo. Sporting a blonde wig and, inevitably, a pink tracksuit, Colley becomes a caricature of every broad-vowelled, nosey neighbour waiting for the chance find something not right about the ‘different’ people over the road – and he does it exceptionally well. Sharon’s appearances are relatively short but subtly, satirically, telling.

Designed by Jeremy Allen, the set is the living room of Zadie and Vimsy’s home. It is minimalist, but colourfully effective. The wide sill of the central window allows Sharon to peer over inquisitively, Stekkie to enter stealthily, and doubles as the roof top where the sisters and Leroy sit to watch the night sky.

Verity Hampson and Benjamin Pierpont obviously relish the creative lighting and sound opportunities a play such as this suggests. Together they bring the sound of Africa, the light of Australia and the suggestion of the metaphysical to spark the senses of the audience.

Marillier hangs the themes of her play like “g-strings on a clothesline”, which Okenya spins skilfully to reveal a diverse coming-of-age story seen though a differently coloured lens. A story told succinctly yet evocatively, with subtlety and humour – and a lot of joy.

Also published in Stage Whispers magazine