Music and Lyrics by Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus. Book by Catherine Johnson. Packemin Productions. Directed by Jordan Vassallo and Courtney Cassar. Musical Director: Peter Hayward. Choreography: Sally Dashwood. Riverside Theatre, Parramatta. February 11 – 26, 2022.

Reviewed : 11 February, 2022

What a positive choice to bring Packemin’s loyal audience packing back in to Riverside! Despite QR and Vaccination-checking queues and compulsory masks, Mamma Mia’s opening night crowd filled the theatre with joyous anticipation – and directors Jordan Vassallo and Courtney Cassar and their very talented and energetic cast rose to their expectations! The production is bright, tight, colourful and makes the very most of the comedy and optimism that infuses the plot and the many ABBA hits.

After the pandemic of setbacks that have affected the arts over the past two years, including Packemin’s rueful need to abandon a production of Wicked, it was an inspiration to reprise their celebrated 2019 production of this lively, foot-tapping, nostalgia-arousing musical. A host of enthusiastic – and stage starved – performers, including some of the lead stars of the 2019 production, have braved a carefully organised Covid safe rehearsal period to bring the happiness of this musical back to Parramatta.

Louise Symes and Courtney Bell reprise the mother and daughter roles of Donna and Sophie. Lithe and petite, but with powerful voices that belie their stature, they inhabit these roles with exuberant joy. Symes is loving and concerned as a caring single mother, fiercely protective of her own independence and suitably ‘peppy’ as part of her old trio, Donna and the Dynamos. She has a wide range and incredibly strong vocal control, especially evident in a moving rendition of “The Winner Takes All”.

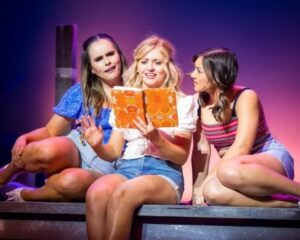

Courtney Bell finds both the naivety and wistfulness of Sophie in her search for her father – and her concern at the Pandora’s box she has opened by inviting the three men mentioned in her mother’s diary to her wedding. From her opening “I Have a Dream”, she takes Sophie through a prolific number of scenes, songs and routines with beguiling vivacity and belief.

The three ‘possible’ fathers – Sam (Scott Irwin), Bill (Mark Simpson) and Harry (Nate Jobe) – provide the “exposition”! Irwin, as architect Sam, rejected 20 years ago by Donna, is serious and soberingly restrained. Simpson’s interpretation of Bill, the Australian writer and adventurer, is laid back and warm. Jobe, as the gay London banker, Harry, makes the most of the slightly over-the-top physicality incorporated into the role. All have strong, compelling voices that adapt easily to the variety of the music. All relate well with both Symes and Bell in the short but poignant emotional moments that add depth to the plot.

Debora Krizak and Rachel Gillfeather are Donna’s Dynamo sidekicks and they both bring to the production a bright oomph and … well … dynamism! Both have excellent comic timing and play off each other skilfully. Both have strong voices and move well. Both are also good actors and bring extra chutzpah and dimension to the roles.

Krizak relishes the innuendos built into the dialogue, especially in the lyrics and the directors’ blocking of “Does Your Mother Know”. Gillfeather relates well with an audience. She is animated, expressive, and light on her feet. Her energy and comedic timing with Simpson in “Take a Chance On Me” are memorable.

Sophie’s fiancé, Sky, is played by the very versatile Joe Kalou. Singer, dancer, actor , musician, Kalou makes more of this role than would seem evident from the script. He finds the joy of his relationship with Sophie, the fun of a stag night, the concern of someone who is thoughtful and mature – and the energy and skill of a seasoned performer.

Enough of the characters! What about the direction and the music? Vassallo and Cassar and musical director Peter Hayward bring a wealth of experience across the performing arts to the company. They have given this production verve, colour and a strong balance of pace and tempo. Choreographer Sally Dashwood has moved over 50 performers in a variety of moves that look spectacular, but take into consideration numbers, space, timing, pace and effect. No easy task, but one she achieves seamlessly.

And what about those 42 performers who make up the ensemble – and the voices that sing from ‘the pit’ so beautifully in numbers such as “S.O.S.”? There is a range of age, experience and diversity in this pretty special ensemble. They bring the fictional Greek island of Kalokairi to colourful, musical life. Their timing is excellent, their enthusiasm boundless. What a great opportunity for all of them to shake off the blues of lockdowns, isolation – and the threat of a vicious virus.

Thank you producer Neil Gooding, your talented creative team and your resilient company of performers for bringing this cheerful, optimistic musical back to the Riverside stage. There will be hundreds of happy audience members singing along in your praise over the next two weeks.

Also published in Stage Whispers magazine

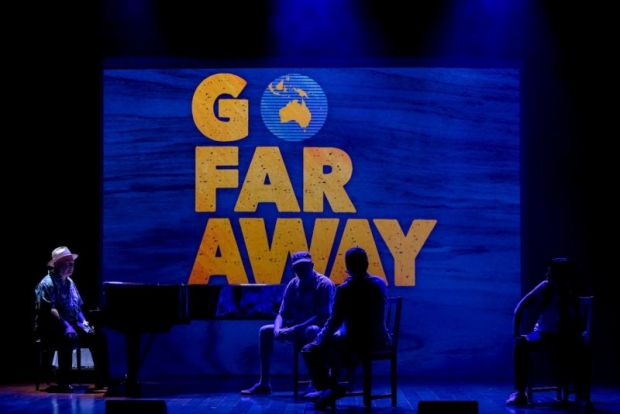

The first sketch, “Go Far Away”, is one that hits hard. It poignantly commemorates the 20-year anniversary of the ‘Tampa’ debacle, our cruel rejection of the survivors, and their detention on Christmas Island – a very different “Welcome to the Rock” than that portrayed in Come From Away.

The first sketch, “Go Far Away”, is one that hits hard. It poignantly commemorates the 20-year anniversary of the ‘Tampa’ debacle, our cruel rejection of the survivors, and their detention on Christmas Island – a very different “Welcome to the Rock” than that portrayed in Come From Away.